The following is an article on immigration to the region by Atlantic Provinces Economic Council President &CEO Finn Poschmann.png)

The Case for More Bodies

July 11, 2016

Every once in a while, governments get something right.

In this case, it is a federal-provincial initiative involving the four Atlantic premiers and senior federal ministers, called the “Atlantic Growth Strategy.” It contains the necessary catchphrases such as clean growth, innovation and infrastructure, but it also contains something readily tangible – an immigration pilot program.

The scheme will operate on top of the provincial nominee program – the provincially-driven program that fast-tracks identified individuals with job offers to permanent residency – and will allow up to 2,000 additional immigrants and their families in to the Atlantic region each year for three years. If successful, the program will be continued and expanded, according to federal immigration minister John McCallum. The notion that this approach might “work” comes from a plan to coordinate the activities of multiple levels of government, schools and employers with the aim of ensuring that immigrants land and find economic success. Strangely, this is a new idea, and one that draws on recent experience in landing and settling Syrian refugees.

And, Lord knows, the Atlantic region needs bodies.

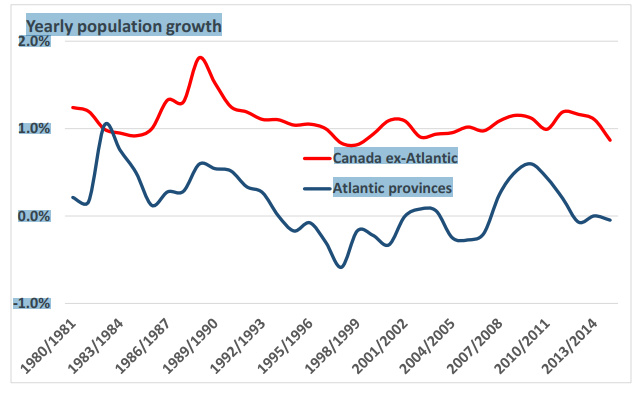

In the region, natural population growth slowed markedly in the early 1990s, and turned negative during the course of 2012. Since 1991, the Atlantic provinces’ annual population growth rate averaged 0%, and total population growth has likewise been zero over the period. Together with demographic aging, this makes sustaining public finances, or pensions, no fun at all.

Now, the natural rate of population increase depends on the lifetime fertility rate of provincial residents. Because the Atlantic provinces’ total fertility rate is less than the Canadian average – and trends in fertility do not shift easily – immigration is tremendously more important to future population growth in the region than it is elsewhere.

Immigration, even at levels many times higher than Canada has seen in recent decades, cannot meaningfully affect the age structure of Canada’s population. In the Atlantic, however, even a comparatively small number of immigrants that are attracted and retained can make an important difference to population growth trends.

Atlantic Canada in 2014/15 accounted for 6.6 percent of the total Canadian population, but accounted for only 3.2 percent of new immigrants. Were Atlantic Canada to have matched the Canadian average for immigrant attraction and retention relative to the resident population over any sustained period in recent decades, the region’s population and population growth rate would be trending upward, rather than flat or down.

In other words, a few thousand people goes a long way ‘round these parts, and the pilot program is welcome.

So what’s the catch?

First, it is not news that economic growth in the region has been sluggish, to put it mildly. Among Canada’s ten provinces, for instance, guess which four have unemployment rates above 8%? Which four provinces have the lowest employment-to-population ratios?

Rural residents in the region, like many in the rest of Canada, might look at the levels of unemployment and underemployment and wonder where the case is for more bodies. Federal officials have long been known to wonder the same thing.

Employers, however, see things otherwise. They search high and low for skilled bodies, for the knowledge and experience they need, and they routinely find themselves looking abroad. This scenario plays itself out across the region, urban and rural, for large and small businesses.

Many employers have to complete Labour Market Impact Assessments, which require them to prove a negative – that no Canadian worker is available to do the job. This pedantic exercise is something that federal policy could usefully shed.

For many employers and in many communities, access to fresh bodies is the number one concern. That speaks to the likely success of the immigration pilot, at least from a hiring perspective.

Then there are the self-inflicted impediments to bringing in and keeping new immigrants.

Cultural insularity is one of them, and not one that governments are well placed to deal with. Yet Treasury Board president Scott Brison’s recent proclamation that the dismissive phrase “come-from-way” should be banished from Atlantic idiom resonated across the country. Attitudes within communities change slowly, with exposure to people and ideas, but they change.

What provincial governments can do, even if it also will take time, is fix the fiscal mess that immigrants to the region meet on arrival. True, Quebec wins for highest overall personal income taxes, but New Brunswick and Nova Scotia and PEI have achieved 50%-plus tax rates for professional income earners. The region has the highest consumption taxes in the country, and the four highest corporation income tax rates. Provincial per capita debt in Newfoundland and Labrador and in New Brunswick is downright ugly.

This is finely targeted foot-shooting. The bright side is that governments have become aware of it.

At bottom, however, is good news. That Canada needs more immigrants, that immigrants are a new positive for our economy, is becoming a widely accepted notion. It is nice, too, to see policy reflect reality.

0

Log In or Sign Up to add a comment.- 1

arrow-eseek-eNo items to displayFacebook Comments